A range of shirts, pants, socks and accessories sold in specialist camping and fishing retailers claim to protect against mosquito bites for various periods.

In regions experiencing a high risk of mosquito-borne disease, insecticide treated school uniforms have been used to help provide extra protection for students.

During the 2016 outbreak of Zika virus in South America, some countries issued insecticide-treated uniforms to athletes travelling to the Olympic Games.

Some academics have even suggested fashion designers be encouraged to design attractive and innovative “mosquito-proof” clothing.

But while the technology has promise, commercially available mosquito-repellent clothing isn’t the answer to all our mozzie problems.

Some items of clothing might offer some protection from mosquito bites, but it’s unclear if they offer enough protection to reduce the risk of disease. And you’ll still need to use repellent on those uncovered body parts.

First came mosquito-proof beds

Bed nets have been used to create a barrier between people and biting mosquitoes for centuries. This was long before we discovered mosquitoes transmitted pathogens that cause fatal and debilitating diseases such as malaria. Preventing nuisance-biting and buzzing was reason alone to sleep under netting.

Bed nets have turned out to be a valuable tool in reducing malaria in many parts of the world. And they offer better protection if you add insecticides.

The insecticide of choice is usually permethrin. This and other closely related synthetic pyrethroids are commonly used for pest control and have been assessed as safe for use by the United States Environmental Protection Authority, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority and other regulatory bodies.

New technologies have also allowed for the development of long-lasting insecticidal bed nets, offering extended protection against mosquito bites, perhaps up to three years, even with repeated washing.

Mosquito repellent clothing

Innovations in clothing that prevent insect bites have primarily come from the United States military. Mosquito-borne disease is a major concern for military around the globe. Much research funding has been invested in strategies to provide the best protection for personnel.

Traditional insect repellents, such as DEET or picaridin, are applied to the skin to prevent mosquitoes from landing and biting.

While permethrin will repel some mosquitoes, treated clothing most effectively works by killing the mosquitoes landing and trying to bite through the fabric.

Clothing treated with permethrin has been shown to protect against mosquitoes and ticks, as well as other biting insects and mites. For these studies, clothing was generally soaked in solutions or sprayed with insecticides to ensure adequate protection.

Fabrics factory-treated with insecticides, as used by many military forces, are purported to provide more effective protection. But while some studies suggest clothing made from these fabrics provide protection even after multiple washes, others suggest the “factory-treated” fabrics don’t provide greater levels of protection than “do it yourself” versions.

Overall, the current evidence suggests insecticide-treated clothing may reduce the number of mosquito bites you get, but it doesn’t offer full protection.

More research is needed to determine if insecticide-treated clothing can prevent or reduce rates of mosquito-borne disease.

Better labelling and regulation

All products that claim to provide protection from insect bites must be registered with the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. This includes sprays, creams and roll-on formulations of repellents.

Anything labelled as “insect repelling”, including insecticide treated clothing, requires registration. Clothing marketed as simply “protective” (such as hats with netting) doesn’t. This approach reflects the requirements of the US EPA.

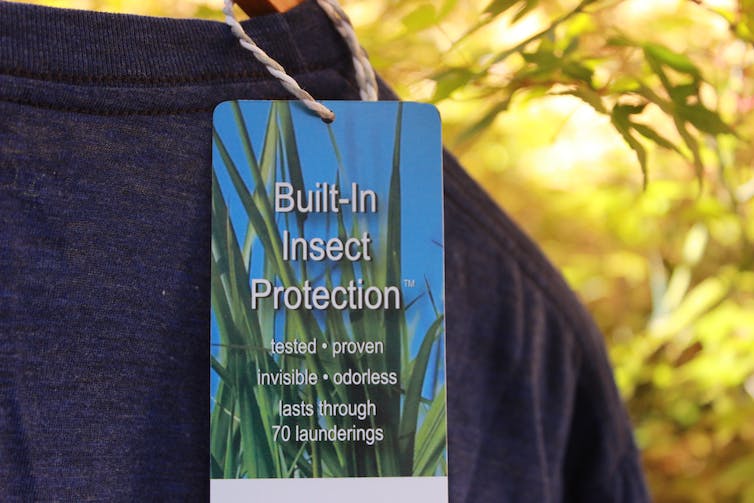

If you’re shopping for insect-repellent clothing, check the label to see if it states that it is registered by the APVMA. You should see a registration number and the insecticide used in the fabric clearly displayed on the clothing’s tag.

While some products will be registered, there are still some concerns about how the efficacy of mosquito bite protection is assessed.

There is likely to be growing demand for these types of products and experts are calling for internationally accepted guidelines to test these products. Similar guidelines exist for topical repellents.

Finally, keep in mind that while various forms of insecticide-treated clothing will help reduce the number of mosquito bites, they won’t provide a halo of bite-free protection around your whole body.

Remember to apply a topical insect repellent to exposed areas of skin, such as hands and face, to ensure you’re adequately protected from mosquito bites.![]()

And if you live in a mozzie or tick prone area, get in touch with TickSafe & Mozzie Team to see how you can get your property rid of mozzies and ticks.

Cameron Webb, Clinical Lecturer and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.